EU Calls Emergency Summit After Trump’s Greenland Threats and New Tariff Warning

The European Union has entered a new episode of transatlantic tension after U.S. President Donald Trump explicitly linked the Greenland file to a new set of additional customs tariffs targeting several European states. In Brussels, the response came quickly: EU leaders are preparing an extraordinary summit aimed at setting a common line at a time when political pressure is blending directly with economic instruments. In parallel, NATO has been pushed to the forefront, and discussions about a possible European trade response have begun to take shape. At the center of this picture lies the EU’s reaction to U.S. threats and the essential question of the coming days: how far is Europe willing to go to deter a dangerous precedent?

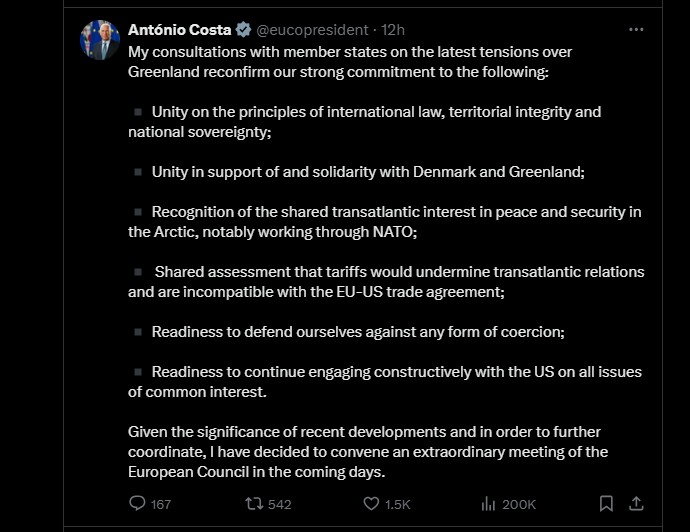

Emergency summit in Brussels: the EU aligns its stance on the Greenland file

The decision to convene an extraordinary summit shows that Brussels is treating the crisis as more than a war of words. The stakes are twofold: protecting a member state (Denmark) and defending the principle of territorial integrity in an increasingly contested geopolitical space: the Arctic.

European Council President Antonio Costa announced that EU leaders will meet “in the coming days,” with talks expected to take place in Brussels. Behind the scenes, ambassadors from the 27 member states have already begun consultations to calibrate options, ranging from diplomatic responses to potential economic countermeasures.

The meeting is expected to be scheduled for Thursday, 22 January, in an effort to quickly build a common position before tensions turn into a spiral of retaliation, according to HotNews.ro.

The tariff threat and the “sale of Greenland” stake: what Washington demanded

At the core of the crisis is the pressure formula used by Trump: an “agreement” for the “full and complete sale of Greenland,” accompanied by cascading trade sanctions if no outcome emerges. In messages cited by the international press, tariffs would be introduced from 1 February (10%), with a possible increase to 25% from 1 June if the deal demanded by the White House is not reached.

The announced targets include Denmark and other allied European states: Germany, France, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Norway, Finland, and Sweden. This detail matters because it suggests a fragmentation tactic: pressure is not directed solely at Copenhagen, but at a broad group of European capitals, with an “economic contagion” effect.

By contrast, Greenland—an autonomous territory within the Kingdom of Denmark—has repeatedly signaled that it does not want to become part of the United States. Beyond political statements, local realities (a population under 60,000) heighten the sensitivity of the issue: an “external” decision about the island’s future would strike directly at the idea of self-determination that Europe frequently invokes in its foreign policy.

Economic retaliation on the table: €93 billion in tariffs or limited access to the single market

In the first hours after the announcements, the European discussion moved quickly into the “deterrence playbook”: if the pressure is economic, the response can also be economic. Two options have begun to take shape in EU consultations: a reply through tariffs on U.S. imports estimated at €93 billion, and an even tougher option by restricting U.S. companies’ access to the European single market.

The first option would hit traditional trade flows: goods, supply chains, and sectors where American companies have a strong presence in the European market. The second option would go beyond customs duties and target directly the ability of U.S. firms to operate, sell services, or compete in certain regulated segments—within an economic area that remains one of the largest markets in the world.

In this logic, the EU anti-coercion instrument (Anti-Coercion Instrument) also comes into play—a legal mechanism designed precisely for situations in which a third country tries to force a political decision through threats or measures affecting trade or investment. In short, the EU has a framework that can gradually lead to targeted countermeasures, following an assessment and de-escalation efforts. The European Commission describes the instrument as a way to protect the “sovereign choices” of the EU and its member states against economic coercion.

For the business environment, the implicit message is clear: the dispute is no longer purely geopolitical; it risks spilling into costs, market access, and predictability. For consumers, any trade escalation has the potential to translate into higher prices and additional strain in an already sensitive economic context.

Within this broader picture, the EU response to customs tariffs becomes a test of cohesion: tough measures require majorities and political consensus that, traditionally, is difficult to build when the economic impact is unevenly distributed among states.

NATO enters the equation: Mark Rutte’s meeting with Denmark and Greenland

While the EU manages the political and economic components, NATO is inevitably drawn into the discussion through the security argument invoked by Washington. In this context, NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte has scheduled a meeting in Brussels with ministers from Denmark and Greenland amid the escalating dispute. At NATO headquarters, Greenland’s foreign minister Vivian Motzfeldt and Denmark’s defense minister Troels Lund Poulsen are expected, without a press conference announced in advance, according to Digi24.

The meeting is relevant not only as a symbol but as an institutional signal: the alliance is trying to prevent a dispute among allies from becoming a strategic fracture. In addition, Europeans insist that Arctic security can be strengthened through allied cooperation without changes of sovereignty. This is, in fact, a key point: if the American argument is “strategic necessity,” the European response seeks to be “the same necessity, but solved within the existing framework.”

Scenarios for the coming days: Davos, negotiations, and the test of European solidarity

The next week brings a calendar that could either accelerate or defuse the crisis. On the one hand, the extraordinary EU summit is designed as a platform for political alignment. On the other, the World Economic Forum in Davos offers an informal setting where leaders can test negotiation channels and recalibrate public messages. In European logic, the retaliation options discussed these days could be used as leverage in dialogue, not as an end goal in themselves.

A “controlled de-escalation” scenario would imply a return to more cautious language, possibly by separating the Greenland file from trade instruments. In an “escalation” scenario, tariffs take effect, the EU responds with mirrored measures or restrictions, and the tension moves from politics into the economy—where inertia and industrial interests make compromises harder.

Domestically, Europe also has a credibility stake: if it accepts that a territory linked to a member state can become a bargaining chip in trade negotiations, it sends a risky signal about how much the principles it invokes are worth in practice.

What the Greenland crisis could change in the long run: the Arctic, resources, and the new strategic competition

Regardless of the pace of the coming days, the episode has the potential to leave strategic marks. The Arctic has been, for years, an increasingly important space: more accessible maritime routes, growing interest in resources, military infrastructure, and competition among major powers. In this context, Greenland gains both symbolic and practical value: a security piece, but also a test of international governance.

For the EU, the crisis could produce two structural effects. First: accelerating debates on strategic autonomy and on the capacity to respond in a unified way to external pressure. Second: reshaping the EU–U.S. relationship in an area where, until recently, the default reflex was almost automatic cooperation.

For NATO, the case could become an institutional precedent: how do you manage a major divergence among allies without fueling fractures that geopolitical adversaries could exploit?

For European public opinion, the Greenland file poses a simple and uncomfortable question: when the economy is used as a tool of political coercion, who actually controls sovereign decisions? In the weeks ahead, the answer will depend on how coherent Europe remains and how credible its message becomes about Arctic security and the limits of economic pressure in relations among allies.